Queer desire from Sappho to Serapiakos

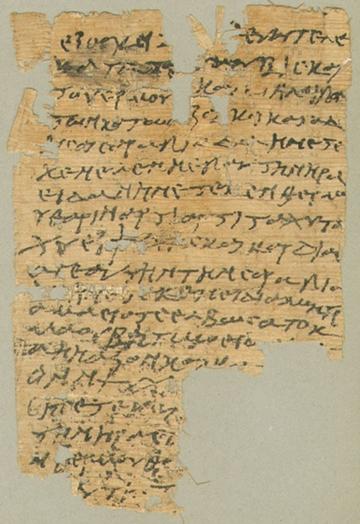

Figure 1: PGM XXXII = P. Hawara 312r. Photo: © Department of Greek and Latin, University College London.

Voices of queer desire have been with us for millennia. For Pride, we offer a selection of voices from the ancient Mediterranean and Near East. From fragments of the love elegy of Sappho of Lesbos to a love spell by Serapiakos from Hawara in Egypt. The urgency and vitality of their queer desire still resonate today.

In her recent novel After Sappho, Selby Wynn Schwartz reminds us of Sappho’s continued power to captivate:

Who was Sappho? No one knew, but she had an island. She was garlanded with girls. She could sit down to dine and look straight at the woman she loved, however unhappily. When she sang, everyone said, it was like evening on a riverbank, sinking down into the moss with the sky pouring over you (Schwartz 2022, 9).

In our present era, queer voices—particularly trans and non-binary ones—are under attack. These voices matter and should be heard. Likewise, it is important to recognise and listen to the many queer voices that came before.

Selected Voices

“Queer desire” here describes desires other than heterosexual or cisgender. Such desire is typically identifiable in the ancient sources by the presence of gendered names and pronouns (e.g., in Latin, female names typically end in -a and male ones in -us; in Ancient Greek, female names typically end in a vowel or -ou and male ones in -s). We see this, for example, when Sappho expresses desire for Anaktoria (fr. 16), Catullus for Iuventius (48), and Lucian’s Megillus for Leaena (Dialogues of the Courtesans 5.3–4). Many ancient authors or their characters voiced their desire for people of a range of genders.

The ancient sources are presented below in English translation and without commentary. Translators are listed in the references.

N.B. 1) If you click on an ancient author’s name, it will take you to the relevant Oxford Classical Dictionary entry for more information. 2) It is important to acknowledge that ancient authors had perspectives that we might consider uncomfortable or unethical on, for example, consent, enslavement, pederasty, or sexual violence. By including an ancient source here, we do not imply that its author’s views should be endorsed. 3) Many thanks to those who offered feedback on this entry.

Sappho

(Greek female poet, c. 630–570 BCE, from Lesbos)

Sappho, fragment 16, translated by Carson 2002:

Some men say an army of horse and some men say an army on foot

and some men say an army of ships is the most beautiful thing

on the black earth. But I say it is

what you love.

Easy to make this understood by all.

For she who overcame everyone

in beauty (Helen)

left her fine husband

behind and went sailing to Troy.

Not for her children nor her dear parents

had she a thought, no—

]led her astray

]for

]lightly

]reminded me now of Anaktoria

who is gone.

Sappho, fragment 31, translated by Carson 2002:

He seems to me equal to gods that man

whoever he is who opposite you

sits and listens close

to your sweet speaking

and lovely laughing—oh it

puts the heart in my chest on wings

for when I look at you, even a moment, no speaking

is left in me

no: tongue breaks and thin

fire is racing under skin

and in eyes no sight and drumming

fills ears

and cold sweat holds me and shaking

grips me all, greener than grass

I am and dead—or almost

I seem to me.

But all is to be dared, because even a person of poverty

Anacreon

(Greek male poet, active late sixth century BCE, from Teos)

Anacreon, fragment 357 PMG, translated by Bernsdorff 2020:

Lord, with whom frisky Eros and the blue-eyed Nymphs and purple

Aphrodite play and you roam the lofty summits of the mountains,

I supplicate you, come to us with kindly favour, and hear my prayer and find

it gracious. Be to Cleobulus a good adviser, and admit my Eros (to your play),

Dionysus.

Anacreon, fragment 359 PMG, translated by Bernsdorff 2020:

Cleobulus is the one I love,

Cleobulus I am crazy about,

Cleobulus I am staring at.

Anacreon, fragment 360 PMG, translated by Bernsdorff 2020:

Boy with the girlish glance, I seek you, but you do not listen, not

knowing that you hold the reins of my soul.

Theognis

(Greek male poet, active c. sixth century BCE, from Megara)

Theognis 1091–94, translated by Gerber 1999:

My heart is in turmoil with regard to your friendship, since I can neither hate nor love you, realizing that it is difficult to hate, when a man has a friend, and difficult to love when he is unwilling (to love you).

Nossis

(Greek female poet, active c. 300 BCE, from Locri)

Nossis, fragment 1 (GP), translated by Skinner 2001:

Nothing is sweeter than desire. All other delights are second.

From my mouth I spit even honey.

Nossis says this. Whom Aphrodite does not love,

knows not her flowers, what roses they are.

Nossis, fragment 4 (GP), translated by Skinner 2001:

Let us go to Aphrodite’s temple to see her statue,

how finely it is embellished with gold.

Polyarchis dedicated it, having made a great fortune

out of the splendour of her own body.

Meleager

(Greek male poet, active 100 BCE, from Gadara)

Meleager, AP 12.63, translated by Paton 1918, modified:

In silence Heraclitus speaks this line in his eyes:

“I will set ablaze even the lightning of Zeus.”

And Diodorus utters this in his breast:

“I melt even a stone warmed by my skin.”

Wretched is he who has received a torch from the eyes of one,

And from the other a sweet fire, smouldering with desire.

Quintus Lutatius Catulus

(Roman male poet and consul in 102 BCE)

Lutatius Catulus, fragment 1 FPL, translated by Heyworth 2015, modified:

My soul has fled. I believe, as usual, it has gone off to Theotimus. That’s it; it has that refuge. What if I had not given an interdiction that he was not to allow that fugitive into his house, but instead to throw him out? We shall go and search. But I fear that we may be caught too. What am I to do? Give me guidance, Venus.

Catullus

(Roman male poet, 84–c. 54 BCE, from Verona)

Catullus 48, translated by O’Hearn 2020, modified:

Your honeyed eyes, Iuventius,

if anyone would allow me to go on kissing,

I would go on up to three hundred thousand times,

nor would I ever be sated, not ever,

not if the crop of our kisses

were denser than dry ears of wheat.

Lucian

(Greek male author, active late second century CE, from Samosata)

Lucian, Dialogues of the Courtesans 5.3–4, translated by Sidwell 2004, modified:

Leaena [female sex worker]: First off, they started kissing me like men. It wasn’t just lip-to-lip stuff. They were opening their mouths, cuddling me and feeling my breasts. Demonassa even bit me while she was kissing. I had absolutely no idea what was going on. Eventually Megilla* got all hot and bothered and took off her wig—it was very realistic and close-fitting. She was close-cropped like one of those really masculine athletes. I was taken aback when I saw this. But she said, “Leaena, have you ever seen such a beautiful young man?” I replied, “Well, Megilla, I don’t see any young man here.” “Don’t make me a woman,” she said, “I’m called Megillus and I’ve been married for ages to Demonassa here. She’s my wife.”

I laughed at this, Clonarion, and said, “So, Megillus, you’ve fooled the lot of us. All the time you’ve been a man, hiding like Achilles among the maidens. And I suppose you’ve got that thing men have and do Demonassa with it like the fellows?” “No, I haven’t got one of those, Leaena. But I’ve absolutely no need of one. You’ll see me using a special technique, much more pleasurable by far.” I replied, “Good grief, are you a hermaphrodite, then, with both sets of organs? They say there’re lots.” At this point, Clonarion, I was still in the dark. “No,” she said, “but I’m a man, none the less.”

And then I said, “I heard the Boeotian pipe-girl Ismenodora telling a local story. Apparently, there was someone in Thebes who changed from a woman to a man. The same fellow was also a fabulous seer. His name was Tiresias. Is this the sort of thing that happened to you too?” “No, Leaena,” she said. “I was born the same as the rest of you. But my way of thinking and my desire and everything else about me are the same as a man’s.”

[*Leaena uses feminine word forms for Megillus throughout the tale. Megillus’ claim to a masculine gender despite the misgendering in the text resonates with modern trans experiences]

Graffiti

(before 79 CE, Pompeii, Italy)

CIL IV 1256:

Sabinus, my beauty, Hermeros loves you.

CIL IV 4485:

Hecticus, baby, Mercator says hi to you.

CIL IV 8321a:

Chloe greets Eutychia: You don’t care about me, Eutychia. With a firm hope you love Ruf(?).

Greek Magical Papyri

(c. second to third century CE, Hawara, Egypt)

PGM XXXII, translated by O’Neil in Betz 1986 (Herais’ love spell for Sarapias [female names]; fig. 1):

“I adjure you, Evangelos, by Anubis and Hermes and all the rest down below; attract and bind Sarapias whom Helen bore, to this Herais, whom Thermoutharin bore, now, now; quickly, quickly. By her soul and heart attract Sarapias herself, whom [Helen] bore from her own womb, MAEI OTE ELBŌSATOK ALAOUBĒTŌ ŌEIO … AĒN. Attract and [bind the soul and heart of Sarapias], whom [Helen bore, to this] Herais, [whom] Thermoutharin [bore] from her womb [now, now; quickly, quickly].”

PGM XXXIIa, translated by O’Neil in Betz 1986 (Serapiakos’ love spell for Amoneios [male names]):

“As Typhon is the adversary of Helios, so inflame the heart and soul of that Amoneios whom Helen bore, even from her own womb, ADŌNAI ABRASAX PINOUTI and SABAŌS; burn the soul and heart of that Amoneios whom Helen bore, for [love of] this Serapiakos whom Threpte bore, now, now; quickly, quickly.” “In this same hour and on this same day, from this [moment] on, mingle together the souls of both and cause that Amoneios whom Helen bore to be this Serapiakos whom Threpte bore, through every hour, every day and every night. Wherefore, ADŌNAI, loftiest of gods, whose name is the true one, carry out the matter, ADŌNAI."

***

These and similar voices have drawn many queer people to the study of the ancient Mediterranean and Near East. In these fragments of ancient yearning, we glimpsed something of ourselves:

…we cherished every word, no matter how many centuries dead (Schwartz 2022, 10).

Lewis Webb

Departmental Lecturer in Classical Sexuality and Gender Studies, Faculty of Classics and Worcester College

Fulford Junior Research Fellow and Stipendiary Lecturer in Classics, Somerville College.

References

Bernsdorff, H. (2020), Anacreon of Teos: Testimonia and Fragments (Oxford).

Betz, H. (1986), The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation: Including the Demotic Spells (Chicago).

Carson, A. (2002), If not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho (New York).

Gerber, D. (1999), Greek Elegiac Poetry: From the Seventh to the Fifth Centuries BC (Cambridge, MA).

Heyworth, S. (2015), ‘Lutatius Catulus, Callimachus and Plautus’ Bacchides', The Classical Quarterly 65.1, 390–395.

O’Hearn, L. (2020), ‘Juventius and the Summer of Youth in Catullus 48’, Mnemosyne 74.1, 111–133.

Paton, W. (1918), The Greek Anthology, Volume IV: Book 10: The Hortatory and Admonitory Epigrams. Book 11: The Convivial and Satirical Epigrams. Book 12: Strato's Musa Puerilis. (Cambridge, MA).

Sidwell, K. (2004), Lucian. Chattering Courtesans and Other Sardonic Sketches (London).

Skinner, M. (2001), ‘Ladies’ Day at the Art Institute: Theocritus, Herodas and the Gendered Gaze’, in A. Lardinois and L. McClure (eds), Making Silence Speak: Women’s Voices in Ancient Greek Literature and Society (Princeton).

Schwartz, S. (2022), After Sappho (Norwich).